08/21/2007

Music Home / Entertainment Channel / Bullz-Eye Home

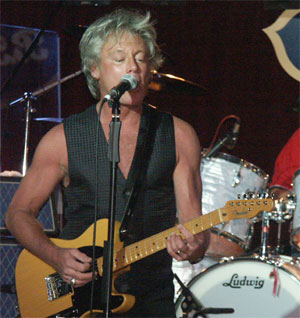

There was a brief period during the 1970s when the funniest rock-related one-liner involved a teenager asking, "Hey, did you hear that Paul McCartney used to be in a band before Wings?" It's a joke that isn't nearly as funny today, what with Wings having been relegated to little more than footnote status in McCartney's career timeline, but if you lived and died by the FM dial during the '70s, you can still see the humor in it. In turn, you might also have been really amused in the late '80s, when kids were thrilling to Eric Carmen's "Hungry Eyes" and "Make Me Lose Control" without having any inkling that, a decade and a half earlier, Carmen had been fronting one of the definitive power pop bands of all time: The Raspberries.

Carmen and his fellow 'Berries -- Wally Bryson, Jim Bonfanti and Dave Smalley -- were staples of the Billboard singles chart from 1972 to 1974, but creative struggles led to line-up changes and the band's eventual dissolution. The 21st century, however, has found the guys getting back together and doing some live dates, one of which – a performance at L.A.'s House of Blues on Oct. 21, 2005 – has recently been released on Rykodisc as Live on the Sunset Strip. After a few scheduling conflicts and one missed opportunity (which was totally this writer's fault), Bullz-Eye had a chance to speak with Carmen recently, and we quizzed him about the legacy of The Raspberries, his solo career and its notable difference to the sound he'd helped forge with the band, and how he can't help but empathize with Kelly Clarkson these days.

First, however, we had to get a good connection. Which is why, moments after Carmen first called, he asked if I minded if he hung up and called me right back.

Bullz-Eye: All right, how's that?

Eric Carmen: Better!

BE: OK, great!

EC: I used my other line, and it's less staticky.

BE: Awesome. Well, as I started to say a moment ago, I'm sorry about the false start a few weeks ago – my mind was just going a million miles a minute – but I am glad that we're finally getting to talk. Live at the Sunset Strip sounds fantastic.

EC: Well, thank you!

BE: And I have to say, with no disrespect to ya'll, that based on a lot of the other live reunion albums popping up now, I wasn't sure what to expect.

EC: Uh-huh.

BE: Did you go into the reunion with a mutual decision that if you didn't feel like you sounded good enough, you wouldn't do it, no matter what the money?

EC: Well, the entire live album was just a spur-of-the-moment decision that happened, literally, three days before we got to L.A. We had no intentions of necessarily recording it. The reunion shows were not exactly a huge budget kind of thing for us, and, as it turns out, a friend of mine, Darian Sahanaja, who is…

BE: …of the Wondermints!

EC: …of the Wondermints, that's right. He e-mailed about three days before we got to L.A. and said, "Would you be interested in Mark Linnett recording the show?" And I said (laughs) "I'd love to have Mark Linnett record the show, but I don't think we can afford to have Mark record the show!" And Darian put me in touch with Mark, and we worked out something, and he came down and said, basically, "I'll just come down and do it, and if you want to buy the audio, I'll sell it to you, and if you want to do something beyond that, we'll work it out, but I won't charge you anything to do it." So he came down and set up – I'd never met him – and we had a really late load-in, thanks to the brilliant House of Blues in Los Angeles, so I literally…the day of the show, our sound check was three hours late…I literally danced through the room, shook Mark's hand, said, "Nice to meet you," and ran on stage. We did a very short sound check and had to race back out again. And the next thing, he sat in a little room and recorded the entire show. And, then, we discussed what we might want to do with it, and we decided that we could get a deal with somebody that made a little bit of sense. It was a project that we really wanted to do for our fans, and for ourselves, just for a little legacy thing. And Mark helped to engineer the deal with Ryko, and then he and I mixed it. He did the physical mixing, and then we talked for about two months every night on the phone until about 2 in the morning, and he would MP3 mixes back and forth to me, and I would critique them, and then we would get on the phone and talk about them some more, and then he would MP3 me another mix. And this went on for awhile. And that's how it came to pass.

BE: So I take it you guys were pleased with the final sound as well.

EC: Yeah! Well, I mean, within the context of the

fact that it was one shot, you know? Most groups that record live reunion

shows will record every night on a 40-city tour and then cherry-pick

the best evening for each song and put it all together, and then they

march it through a ton of overdubs and sweetening, and what you end

up with, often, has very little to do with what they played live. In

this case, this was a one-shot deal, and we dealt with some of the

little idiosyncrasies and problems that can happen because of that,

but in some ways, it makes it a much more honest live album. I mean,

the L.A. show was the one show that we played out of the 10 where we

had what musicians refer to as "gremlins" on stage.

EC: Yeah! Well, I mean, within the context of the

fact that it was one shot, you know? Most groups that record live reunion

shows will record every night on a 40-city tour and then cherry-pick

the best evening for each song and put it all together, and then they

march it through a ton of overdubs and sweetening, and what you end

up with, often, has very little to do with what they played live. In

this case, this was a one-shot deal, and we dealt with some of the

little idiosyncrasies and problems that can happen because of that,

but in some ways, it makes it a much more honest live album. I mean,

the L.A. show was the one show that we played out of the 10 where we

had what musicians refer to as "gremlins" on stage.

BE: Naturally.

EC: Just everything that could go wrong went wrong during the course of that show. We opened each night of the 10 cities that we toured with a 10 to 15 minute montage, a fast-edit career retrospective, and it worked. We never checked it, and it went off like a charm in every one of the nine places that we played prior to L.A.. We got to L.A., and we said, "Check that video to make sure everything's OK." And they did. And, of course, that was the night that it completely screwed up. (laughs) We're sitting backstage and listening to this montage starting to hiccup, and thinking, "Oh, geez. Here we go." All those sorts of things. Mark had never seen us perform, and Jim Bonfanti, our drummer, is a leftie who plays a right-handed kit. So Mark, unknowingly, had miked the wrong cymbal, the wrong ride cymbal. So during the course of the mixes, I kept saying to Mark, "Where's the ride cymbal? I can't hear enough ride cymbal!" And about 10 days into the mixes, he said, "Well, you know, I didn't realize Jim was a leftie, so I actually miked the wrong one, because I'd never seen you guys!" And, then, I further found out that…later on, Jim told me, "Well, about halfway through the show, I cracked that cymbal." And the minute it cracks, it goes dead. So, y'know, within the context of all those sorts of little things, we worked our way through the mixes, and we did what we could to fix things that needed fixing, but every instrument that you hear on this recording was played that night. There were no instrumental overdubs and very little sweetening or fixing or whatever that could be done, because there was only one performance!

BE: How did you duplicate the tinny-radio bit on "Overnight Sensation" for the show? My editor was really impressed by that.

EC: We actually have a sample.

BE: I was wondering about that.

EC: Yeah, on one of our keyboard player's keyboards. And when it comes to that point in the song, he just hits that key, and then we build everything back in ourselves. And the one thing that I've noticed that's interesting live is that, you know, I just start the song – I'm not listening to whatever the timing is on that little sample, but there's really not many ways to do it – and, for some reason, we always seem to be perfectly in time when we hit that spot. It would really be awful if we weren't, but we've just never…it's always been perfect. So that's a good thing.

BE: How did you come up with the final set list, and were there any songs that you tried but that just didn't pan out live?

EC: Not really. We actually kept trimming back the set list, because the first show we played was about two and a half hours, and we played darned near every song that we knew, from all four albums. I mean, we left maybe 10, maybe 12 songs out of the entire catalog, for the first show…because, actually, we'd originally only intended to play one show. It was going to be just the show in Cleveland, to open the new House of Blues here, and that was it. And then that went so well…when they put the tickets on sale, it sold out in four minutes, which completely took them and us by surprise! And then it turned out that half the tickets had been bought by people from other cities who had actually flown in…or from other countries in some cases. People flew in from as far as Japan, England and the Netherlands for this one show, which we found completely incredible, and some continued to follow us around the country as we added the dates here and there. After the first show, the House of Blues said, "Well, geez, how would you guys like to play on New Year's Eve?" And we said, "Well, we're all rehearsed. I guess we could!" (laughs) And then after the New Year's Eve show, they said, "Well, we'd really love you to go up and play the Chicago club in a couple weeks." And we thought, "Well, we like Chicago, even though it's the dead of January! But, sure, we'll go do that!" And Chicago…I thought it was really one of the best dates that we played. It's just such a beautiful, beautiful club. And it just kind of spiraled from there. We went on, played a couple of great shows in New York, and then eventually worked our way out to Los Angeles.

BE: Having checked out the bonus DVD, I have to say, I was very impressed: you pulled off the vest-but-no-shirt look really well.

"When I was writing my second solo album, Boats Against The Current, I used to play Born To Run every day, just to get me started. And when Bruce (Springsteen) and I met the first time, he said, 'Wow, I think I wore out that Raspberries' greatest-hits album!' And I said, 'And, you know, I think I wore out Born to Run!'" EC: (laughs) You know, it's not really my preferred look, but it just gets so darned hot up there! When you're screaming your lungs out for two hours, it's, "What can I wear that will be just the coolest thing I can possibly have on?" I'd love to look into some sort of refrigeration. I went to see McCartney a few years ago, and I was just dumbstruck by the fact that no one on his stage ever had a bead of perspiration on their foreheads (laughs) for two solid hours! I thought, "How did they do that?" There's just gotta be some kind of a cooling system that he's got going on up there, and I wanna know what it is!

BE: Yeah, when you walked out, at first I was, like, "Uh-oh: aging rocker alert!" But, no, you had the performance to back up the look, so I applaud you for that.

EC: (laughs) Well, thank you. It was purely from the standpoint of making it as cold as I could get myself up there. Depending where you are, in about three songs, we're pretty much drenched, so to try to make it through two hours of high intensity screaming and singing and performance? I mean, it gets mighty warm up there!

BE: I know there were several false starts over the years when it came to doing this reunion. Do you know what the impetus was to finally get out there and do it?

EC: Oh, yeah. I had gone out in 2000, after our first false start, which kind of fell apart, basically, because we had promoters at the time who were interested in doing this and had promised us a certain amount of money that we would be able to make per show. And I had been pretty much a stickler for the fact that…we had played so many gigs back in the early '70s, when we were together…where they would just plug us into any cow barn, where they'd plug some microphone into some amplifier, and they'd say, "That's your P.A. system"…between Providence and New York to just fill in a date. And there's just no way that you can sound good under these circumstances, and I just never wanted to revisit that. I said, "If we're ever gonna do this, it's gotta be done right, and that means we've gotta have a good sound system and we've gotta have good lighting." Because people don't know, don't care, and shouldn't have to (pauses). I've talked to bands many times who say that if the sound system is unplugged on the entire left side, and the pedals fall off your piano, the crowd doesn't go off at the end of the show and say, "Gee, their road crew really sucked." They say, "The band sucked!" And they shouldn't have to be accountable for what the road crew did. Things just have to be right, and it costs a certain amount of money just to insure that you've got the proper people on stage to make that happen, and the proper equipment on stage. So, over the years, certain myths had grown up around the band, and I maintained that I never wanted to put us on stage and pop the bubble, and have them say, "Ah, they weren't so great." So I had been kind of holding out for some special situation. When I had toured with Ringo (Starr, as part of his All-Starr Band) in 2000, we played the House of Blues in Chicago and the one in Los Angeles as part of that tour. And the first time I walked out on stage at the House of Blues in Chicago, I thought, "God, what a beautiful room this is! It looks like it was set up for musicians! They have a great sound system in house, great monitors, the lighting is good, the stage is comfortable." And then we did the one in L.A., and I thought, "Wow, this is absolutely great!" So when the House of Blues in Cleveland, that was going to have their grand opening, called to say, "Would you guys consider getting back together and open our club," it was kind of the right time and the right place. And I told Jim Bonfanti, "If we're ever gonna do it, this is where we're gonna want to do this." Because it just took all those problems out of our hair. And it worked out great. It's a good chain of clubs.

BE: So I hear you've been writing some new material. Does that mean that a new Raspberries studio album is a realistic possibility?

EC: (Clearly hesitating to look for the right choice of phrase.) Uhhhhhhh…you know…I don't, uh.

BE: (laughs)

EC: (laughs) Well, the music business is

in such an odd place right now that I, I wouldn't want to make any

guarantees about anything. The thought has crossed my mind that it

would be kind of fun to do a new album with the band now, but, right

now, if you're not a country act or a hip-hop act, it seems to be increasingly

difficult to sell records. Or maybe if you're Hannah Montana, which,

last I checked, was the number two album right now.

EC: (laughs) Well, the music business is

in such an odd place right now that I, I wouldn't want to make any

guarantees about anything. The thought has crossed my mind that it

would be kind of fun to do a new album with the band now, but, right

now, if you're not a country act or a hip-hop act, it seems to be increasingly

difficult to sell records. Or maybe if you're Hannah Montana, which,

last I checked, was the number two album right now.

BE: Ugh.

EC: It's a really weird landscape out there right now, and until this new paradigm shakes out a little bit and people figure out how they're going to change this business … I mean, the CD is basically a dead issue. How are we going to deliver music? What's the pipeline going to be, so that people can get music inexpensively and lots of it? I think that's what's going to happen. When we started out in the early '70s, most acts toured to support their album; you made money on the album, and you maybe broke even on the tour. The paradigm now is completely the opposite. Now, bands can't make any money on the recording because people will just download it and steal it. So, in the future, I wouldn't be at all surprised to see bands giving away their music in the hopes of putting together an audience of faithful followers who will come and see them perform live, and groups are just going to have to make their money on live performances. No one's quite figured out exactly how this is going to work, which is why I'm seeing all of these very creative approaches, like McCartney at Starbucks. And I saw that Joni Mitchell just signed on to do an album with Starbucks! (laughs) So that shows you what kind of a state the industry is in!

BE: Yeah, I'm actually friends with one of the publicists over at Concord Music, who distributes the stuff on the Starbucks label, and he's giddy over the response, because, y'know, they're all diehard music fans over there. It seems surreal that an artist's first line of commercial defense would be to sell their album through Starbucks, but…

EC: But it's true! The Eagles just made a deal for their new album to be an exclusive through Wal-Mart.

BE: On the whole, I'll stick with Starbucks.

EC: I mean, can you believe that? (laughs) Mr. Walden Woods made a deal with Wal-Mart!

BE: You know, I was going to bring up Springsteen in a few seconds anyway, but I was in a press scrum with Steven Van Zandt (of The E Street Band) recently, and he was talking about the change in the music industry, and the big issue as he sees it is that it's back to 1962, and the industry doesn't seem to realize that they're back to the days, pre-Beatles, where singles are the driving force again, and they don't know how to handle it.

EC: It's true. And the odd thing is that, back in 1962, when singles were the driving force, people just bought singles. They didn't even buy albums. But the major labels are still trying to figure out how to make you spend $15 to buy an album, and no one's gonna do it. They can go onto iTunes, download the single for 99 cents, and that's that. Or get the three songs you want, and be done with it!

BE: Well, since I do have an easy segue into Springsteen now, has his admitted love of The Raspberries kept you guys warm at night for all these years?

EC: You know, it's only been in the last couple of years that we became aware of it. I'd heard rumors in the past. We both worked in the same studio – The Record Plant, in New York – and it was kind of right after we did; we were there from '72 to '74, and I think Bruce started in '74 or '75. But we worked with the same engineers in the same studio, and I think Bruce and I are about a month apart, birthdaywise – mine's this Saturday (Aug. 11), and his, I think, is about a month after that (Sept. 23) – so all of us came up at that moment in music. We came of age…I mean, we were 14 in 1964, when The Beatles were on "The Ed Sullivan Show" for the first time, and it had such a huge impact on everything. On the world. In those days, we were coming out of the Pat Boone era, and, all of a sudden, you've got the British invasion, you've got the Ronettes, you've got Motown, and for the first time, music really began to drive the culture. And I think that, throughout the '60s and '70s, it really did. Particularly in the '60s. I mean, The Beatles just changed everything, and that was a really amazing time to be a teenager, and to hear these changes taking place. The difference between hearing Pat Boone's "Tutti Frutti" on the radio and then hearing "I Can See For Miles" (laughs) I mean, it was, like, "WOW! What is THIS?!?" Or "Satisfaction," by The Rolling Stones. This was some big changes going on, and it was all great. And I think it inspired a lot of people, and I think the primary difference between Bruce and me is that he spent more time listening to Dylan, and I spent more time listening to The Beatles! (laughs) But a lot of the other influences are very, very similar, and I hear it in his records. Oddly enough, when I was writing my second solo album, Boats Against The Current, I used to play Born To Run every day, just to get me started. And when Bruce and I met the first time, he said, "Wow, I think I wore out that Raspberries' greatest-hits album!" And I said, "And, you know, I think I wore out Born to Run!" But I think you can see, there are things, if you listen closely. If you listen to "Jungleland," and then listen to The Raspberries' "Starting Over," from our 1974 album, those piano intros sound kind of similar. And we had heard that Bruce had listened to "I Wanna Be With You" and wanted to do an intro kind of like that for "Born to Run." And then I recently read somewhere where someone was talking about they got the idea from "The Locomotion," which is exactly where I took the idea for "I Wanna Be With You" from! (laughs) We actually played "Locomotion" at Carnegie Hall in 1973 because I just loved that record. And when it came time for me to write something, I thought, "Wow, that's a great intro! I think I'll just work that into this song!" And that's how that all works.

BE: Actually, you brought up two things in the last minute that I'd wanted to ask you about, so I'll start with what's probably the quicker of the two. When Starting Over came out, did you view it as a new beginning for the band, or were you thinking, "I really don't know if this new line-up of the band is going to take or not?"

EC: Well, you never know. It was a good band, and,

y'know, I'm by nature an optimistic person -- contrary to some of the

records that I've written -- and you always kind of hope for the best

and dream big. That's always been my motto. You don't shoot for the

bottom of the barrel; you aim high. We sure hoped that that

album would help turn things around, because we had been, as I said

in (his solo song) "No Hard Feelings," "locked in image prison / waiting

for that break," for a long time, and we were desperately trying to

break out of it. And, then, we did the Starting Over album,

and Rolling Stone picked it as one of their seven best of

the year in their annual writers and critics poll, and they picked

"Overnight Sensation" as the best record of the year, and we subsequently

sold the fewest number of copies of any of our records, and played

every hole on the east coast for six or seven solid months of demoralizing

gigging. And that was pretty much the end of it. We realized at some

point that there was no way to climb out. What we had tried to do had

been successful on one level, and a complete bust on another level.

The rock critics got it, and the 16-year-old girls got it, but FM radio

was just not about to play a band that sounded like they were making

singles, and so it was kind of like beating your head against the wall

at a certain point. It was time to move on and try something else.

EC: Well, you never know. It was a good band, and,

y'know, I'm by nature an optimistic person -- contrary to some of the

records that I've written -- and you always kind of hope for the best

and dream big. That's always been my motto. You don't shoot for the

bottom of the barrel; you aim high. We sure hoped that that

album would help turn things around, because we had been, as I said

in (his solo song) "No Hard Feelings," "locked in image prison / waiting

for that break," for a long time, and we were desperately trying to

break out of it. And, then, we did the Starting Over album,

and Rolling Stone picked it as one of their seven best of

the year in their annual writers and critics poll, and they picked

"Overnight Sensation" as the best record of the year, and we subsequently

sold the fewest number of copies of any of our records, and played

every hole on the east coast for six or seven solid months of demoralizing

gigging. And that was pretty much the end of it. We realized at some

point that there was no way to climb out. What we had tried to do had

been successful on one level, and a complete bust on another level.

The rock critics got it, and the 16-year-old girls got it, but FM radio

was just not about to play a band that sounded like they were making

singles, and so it was kind of like beating your head against the wall

at a certain point. It was time to move on and try something else.

BE: And you just mentioned Boats Against the Current, which I finally got to hear for the first time recently, when American Beat Records released it as a 2-fer with Change of Heart.

EC: Oh, wow!

BE: Why is it that so much of your solo material beyond your debut has stayed out of print in the States? I know it's been reissued in Japan before, but…

EC: Probably because no one has gone to Arista on my behalf and said, "Hey, why don't you put these things out?" (laughs) You know, Clive (Davis, founder of Arista Records) is a singles guy, and so he's always looking to repackage a bunch of singles and put it out, but I don't think he especially dug or even got the Boats Against the Current album. We were kind of in sync on the very first album, and then he and I didn't really see eye to eye on a whole lot of things after that. My whole fourth album, he completely ignored! It was like I wasn't even there. I was, like, "Clive? Hello? I've got an album out here!" "No, no, you don't!" And I've recently read in one of the books, I think it was the Marathon Man book (an extremely in-depth Carmen biography, written by Bernie Hogya and Ken Sharp), where he had a quote where he said, "Once you've gone pop, you can't go back." Oh, thank you for writing that in stone for me. I wasn't aware of that! But that was his take: I had gone pop on the first album, so my rock credibility was shot forever, and he wasn't going for it.

BE: Given that a lot of your solo stuff was, shall we say, more mellow than what you'd done in The Raspberries, did you find as time went on that less and less people were even aware that you had been in a band?

"Within the context of the label you're on and the people you're working with, there are times when your hands are kind of tied. I fought the good fight at Arista as much as I could, but at a certain point – as Kelly Clarkson is just finding out – it is futile to continue to be Don Quixote, jousting with the windmill." EC: You know, it's an odd thing. Sometimes, on MySpace or on websites or something…like, I put up a couple of Raspberries songs on my MySpace page the other day, and a couple of people were, like, "Geez, I never even knew you were in that band!" But most people seem to. They sort of did. Or, at least, the ones who have communicated with me. But they were kind of two sides of the same coin, I guess. At Capitol, we released "Go All The Way," and once that became a huge smash, all Capitol wanted from us was "Son of 'Go All The Way.'" And, so, whatever we did outside of that three-minute, up-tempo pop/rock thing was pretty much ignored by the label, and they weren't interested. When I went to Arista, the first single that Arista decided to release – and I agreed with this choice – was "All By Myself." And I think that might've been the first and last time that Clive and I agreed on anything! (laughs) But we were the two boosters of that song, in spite of a lot of other people thinking, "Oh, you should release 'That's Rock N' Roll' first, because it's the obvious, radio-friendly, three-and-a-half-minute, up-tempo thing." But I wanted to do something that was completely different from "Go All The Way" and "Tonight" and whatever. And after "All By Myself" became a huge smash, then, of course, all Arista wanted to hear was "Son of 'All By Myself,'" so I was kind of out of the frying pan and into the fire! And the reality is that I was really very envious, and have been for many years, of artists who were on labels where they could do both things, they could do more than one thing. There are a few labels that come to mind – A&M was one, Columbia another – where they seemed to allow their artists to actually be artists, and you could write a ballad one day, and then they'd put out an up-tempo song as the following single. I wasn't that lucky. The easier thing for most labels to do is to typecast you. "You are the pop/rock guy." Or, "You are the balladeer." And then, to them, if you release something outside of that, it confuses people, and it's hardest for them to promote. They're, like, "Well, this doesn't sound like Eric Carmen," you know?

BE: I had wondered how much of that was you and how much of it was the labels. Like, for instance, my editor wasn't really familiar with The Raspberries, and now he's listened to Live on the Sunset Strip, and he's totally in love with it…

EC: Cool!

BE: …but his first response was, essentially, "I can't believe this is the same guy who sang 'Make Me Lose Control.'"

EC: (laughs)

BE: Because that's his frame of reference, you know?

EC: Yeah, and I understand that, but, y'know, within the context of the label you're on and the people you're working with, there are times when your hands are kind of tied. I fought the good fight at Arista as much as I could, but at a certain point – as Kelly Clarkson is just finding out – it is futile to continue to be Don Quixote, jousting with the windmill. You realize at a certain moment that Clive is going to do what he wants, and you can buck that, and he'll crush you like a bug (laughs) or you can try to get along. And not many acts at Arista Records ever get to do just exactly their thing. If Clive doesn't like it, it's not going to happen. He's an incredible record executive, and his track record is superlative, but he also knows what he wants…and you'd best deliver it.

BE: OK, and I've got just one last one, so I can keep you as close to on track as possible.

EC: Uh-huh.

BE: At what point did you realize that The Raspberries were being worshipped by a whole new generation of power pop bands?

EC: You know, I'm not sure that I ever officially (hesitates). You know, lemme take that back. Somebody sent me a tape of Axl Rose singing a song…actually, it was from my first solo album, a song called "Everything," which was very ballad-y. It was actually an unfinished song on my first album that my producer liked so much that he said, "We just have to record whatever there is of it." And, so, we did. And, all of a sudden, I got this tape years later of Axl Rose – of all the people in the world! – singing this thing live in Australia or New Zealand or somewhere, and I thought, "Wow! He picked a ballad! Of all the things he might've picked!" But, then, as the years unfolded, I found out that there were all these guys…the Motley Crue guys, the guys in Fountains of Wayne and Rooney…that really enjoyed what we were doing. And I thought, "Well, thank goodness!" (laughs) I mean, how wonderful is that, that a new generation has found us? And we were surprised on tour that there were an awful lot of guys in their '20s that looked like musicians at all of our shows. So it's a very cool thing. And when we played New York, Little Steven came, and Jon Bon Jovi came to a show, and Max Weinberg showed up, and we realized, "Y'know, we probably should've been born in New Jersey!" Because New Jersey, apparently, totally got it! But it's been a wonderful thing to learn that young bands and young musicians…which I find more and more now, because I have two children, and my kids are fairly young now, they're 10 and 7…but the teenage kids of friends of mine, their children are all going back and listening to The Beatles. They've got Beatles music on their iPods, and the Stones, and The Who…and I think it's because they have no good music of their own! Or too little or it, anyway. So, yeah, it's all good.

BE: Well, I'm glad we finally got things arranged to chat.

EC: Yeah, it's been good talking to you, too! And, by the way, I look at your website all the time! It was one of the first things somebody sent to me when I got a computer a few years ago. It was, like, "Check this out!" And I think it's a very cool website.

BE: Yeah, it's been expanding all the time. We've really upped the pop culture content.

EC: Absolutely.

BE: And you can tell it's not always the most commercial stuff, and definitely a lot of what the editors like.

EC: Well, that's good, though. See, I wish the music business was more like that. And I guess it's getting more like that. The internet has really opened things up so that, now, you go direct to the public and you find your own niche audience. So that's probably all good, in the grand scheme of things.

BE: Well, we like to think so.

EC: (laughs) All right, Will. Good talking to you.

BE: You, too.